Spotlight 16: Climate change drives hunger in Africa: concrete action needed at COP26

By Ines Schultes, Senior Researcher

The world has made progress in fighting food insecurity and undernourishment over the last decades, however, the number of food insecure and undernourished people has started to rise again in recent years. The COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated an already dire situation. The world and Africa are not on track to meet the global UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the continental goals set out in the African Union’s Agenda 2063 to tackle hunger and ensure food security.

What are food security and hunger?

Food security means that all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their food preferences and dietary needs for an active and healthy life. Food insecurity can be experienced at different levels of severity, from mild, to moderate and severe.

Hunger is usually measured by the prevalence of undernourishment which means that a person is not able to acquire enough food to meet their daily minimum dietary energy requirements over a period of one year.

Facing food insecurity does not necessarily mean someone is experiencing undernourishment too. However, when someone is severely food insecure, they have run out of food and gone a day or more without eating and thus have most likely experienced hunger.

Africa is the world’s most food insecure region

According to the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO), in 2020, 768 million people globally faced hunger and 2.4 billion did not have access to adequate food, 118 million and almost 320 million more, respectively, than in 2019.

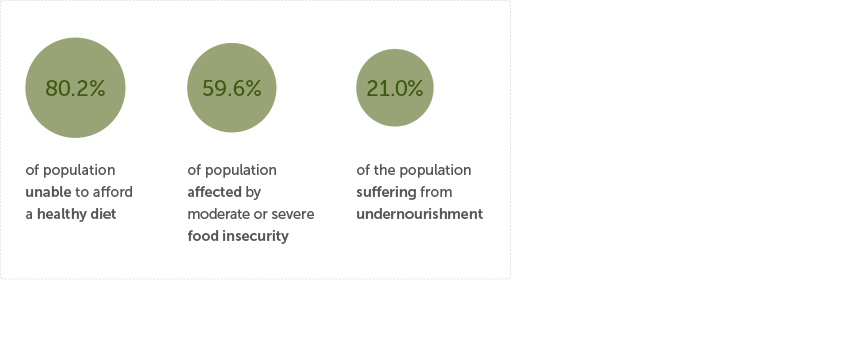

Around 800 million people in Africa, equivalent to about 60% of the continental population, are affected by moderate or severe food insecurity. This is the highest proportions since 2014 and greater than in any other world region.

In 2020, more than one-third (281.6 million) of the world’s undernourished people lived in Africa, an increase of 46.3 million since 2019. This equates to about one in five Africans (21.0%) and is more than double the proportion of any other region.

In Africa, between 2017 and 2019, the costs of a healthy diet increased more than in any other region. And in 2019, around 1.0 billion (80.2%) people on the continent were unable to afford a healthy diet.

Drivers of food insecurity are interlinked and multiplying

Conflict remains the number one driver of food insecurity globally and in Africa, as it interrupts every aspect of food systems including production, supply and consumption. The two other primary drivers are climate and economic slowdowns. Climate variability and extremes heavily impact agricultural productivity, making African countries which are dependent on rain-fed agriculture particularly vulnerable to these events. The global economic downturn resulting from COVID-19 contributed to one of the largest increases in world hunger in decades.

Not only do all three drivers continue to occur more frequently and more intensely but they increasingly appear in combination, leading to multiple and compounding impacts on food systems. The consequences of this are severe. In 2020 at the global level, when countries were affected by economic downturns combined with climate-related disasters and conflict, increases in undernourishment were five times larger than when affected by economic shocks only.

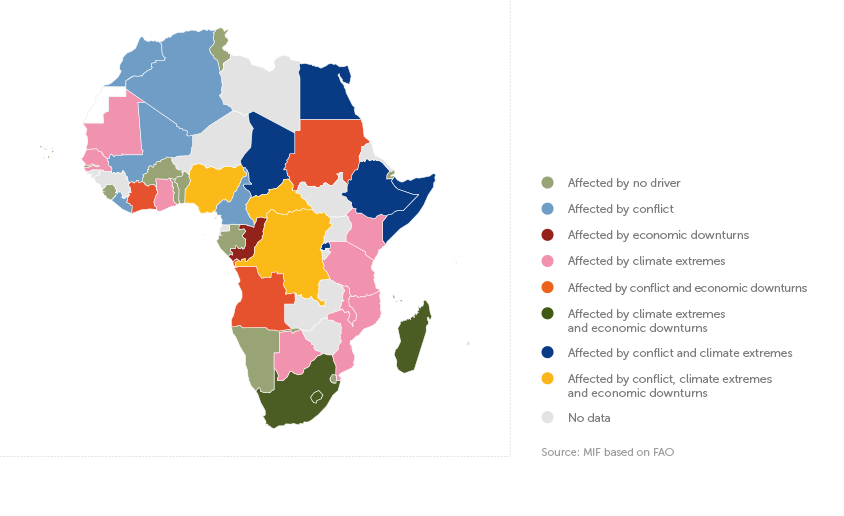

African countries: Combination of drivers of food insecurity (2010-2019)

Research Spotlight series

A new series exploring data and key findings from the 2021 Ibrahim Forum Report.

Multiplier effects are particularly felt in Africa. The continent was the only region where all three drivers (occurring individually or in combination) led to increases in undernourishment between 2017 and 2019. In addition, countries on the continent where drivers occurred in combination faced very high increases in undernourishment.

The most concerning trend for Africa is the intersectionality between conflict and climate events. Hunger on the continent was most frequently driven by this combination of drivers, occurring in five African countries: Chad, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Somalia and Egypt. Central African Republic, DR Congo and Nigeria also faced conflict and climate extremes with the addition of economic downturns. Countries affected by conflict and climate extremes in Africa showed a higher increase in undernourishment than countries affected by the same drivers in other regions.

The world’s first climate famine occurred in Africa and the outlook for the future is grim

The consequences of climate change on hunger are becoming ever more apparent. In 2021, Madagascar was the first country in the world to face a famine solely caused by the consequences of climate change. Year-long periods of drought led to agricultural losses of up to 60 percent in the country’s most populated provinces. The Southern African island produces just 0.01 percent of global carbon emissions.

The situation is not expected to improve in the next few years and the world is not likely to meet its commitment to zero hunger by 2030. While improvements over the next decade are forecasted for Asia, the situation in Africa looks grim. Almost 20 million additional people are expected to face hunger by 2030, bringing the total number to 300 million. 30 million additional people globally are expected to suffer from hunger by 2030 due to the socioeconomic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, with more than half (16.5 million) of those living in Africa. Climate change is forecasted to push an additional 78 million people into chronic hunger by 2050, over half of them in sub-Saharan Africa.

So far, international efforts have fallen short of expectations

Expectations for 2021 on improving food systems and food security were high, with several international events scheduled to tackle the issue, including the UN Food Systems Summit in September. But the conduction and the outcomes of the summit disappointed many. The summit was boycotted by over 600 organisations and individuals over claims it lacked inclusivity and that corporate interests were taking precedence. The outcomes and commitments of the summit are not considered strong enough for a genuine transformation of global food systems while also too little focus was put on nature and climate.

Disappointing progress at the Food Systems Summit increases the pressure for tangible, meaningful and actionable outcomes at COP26. The food security situation in Africa paints a clear picture of the heavy impact the climate crisis is already having on the continent: the region that contributed the least to global warming is being hit the hardest. The world has not yet managed to find a way to mitigate the crisis, let alone reverse it. As climate activist Greta Thunberg pointedly reminded global leaders, there is no more time for “blah, blah, blah”. International efforts need to stop defining and redefining new goals from summit to summit but need to agree on clear commitments and implement concrete measures. COP26 might be the last chance Africa and the world get.