Spotlight 6: Domestic resource mobilisation: Financing a post-COVID agenda

By Ben Chandler, Researcher

Across Africa, many countries are reeling from the holes that COVID-19 has blown in their budgets. In the short term, an immediate liquidity boost - comprised of new Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) and other rapid liquidity facilities - is essential to fund an effective response to the third wave and free up fiscal space going forward, as discussed in a previous research spotlight.

The COVID-19 crisis has exposed the deeper structural issue of limited domestic resource mobilisation. An additional $285 billion is expected to be needed between 2021 and 2025 to finance the recovery, on top of the $200 billion annual financing gap Africa was already facing to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These funds cannot be secured without significantly expanding domestic resource mobilisation.

Increasing taxation capacity is essential

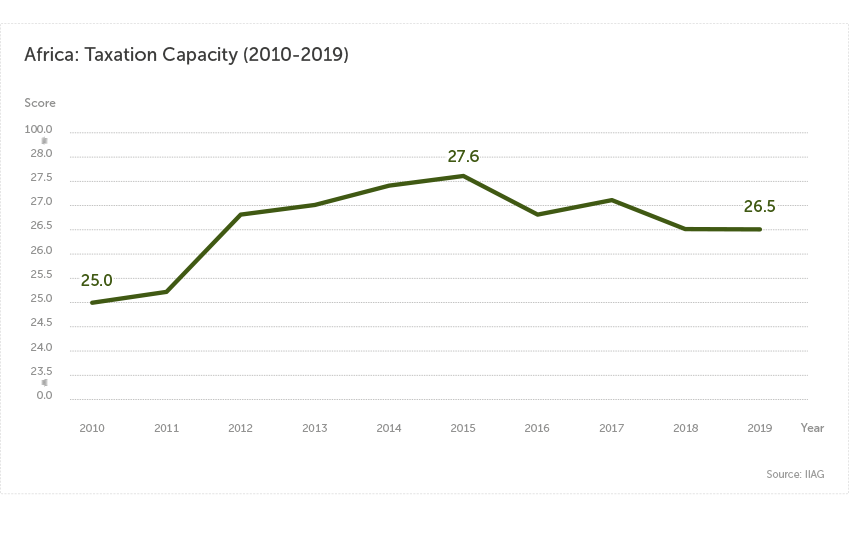

First, the expansion of domestic tax bases is essential. The Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG) shows a decline in taxation capacity in recent years at the African average level. In 2018, an African Tax Administration Forum (ATAF) study found the average tax-to-GDP ratio in Africa to be 16.5%, in comparison to 34.3% across OECD countries. Improving this trajectory will be essential to the long-term recovery and the SDGs.

Research Spotlight series

A new series exploring data and key findings from the 2021 Ibrahim Forum Report.

Domestic resource mobilisation can be expanded through stronger tax administration, better enforcement of tax laws, formalisation of informal trade that leaves many outside the tax pool, and innovative taxes such as the digital services tax being developed by ATAF. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) estimates that improving tax efficiency could raise tax revenue by +3.9% of GDP. Better control of corruption and effective enforcement of existing laws could reduce administrative inefficiencies and raise an additional $110 billion per year in revenue on the continent.

Race to the top, not the bottom

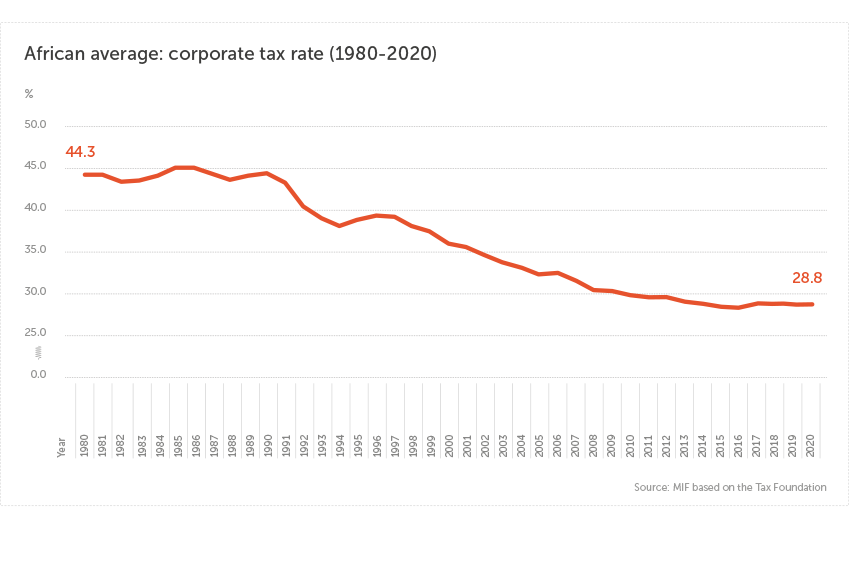

African governments could also increase revenue by raising corporate tax rates and eliminating unnecessary tax exemptions for investors. The prevailing economic worldview of the last four decades that defines all competition as inherently good has prompted a ‘race to the bottom’, with developing countries rushing to lower corporate tax rates and offer tax exemptions to attract foreign direct investment (FDI). While this has increased returns for corporate shareholders, there is little evidence to suggest this strategy has attracted investment. The IMF reported that ‘business surveys conducted in Africa, Asia, and Latin America suggest that tax incentives very often have no impact on the investment decisions of multinationals’. A World Bank Survey of investors in East Africa found 93% would have invested regardless of tax incentives. According to the campaign group ONE, in 2019 in Nigeria, a single tax incentive cost the government $3.2 billion, the equivalent of what it spent on healthcare that year.

Even though factors such as political and economic stability have a greater sway over investor decisions than tax incentives, corporate revenues continue being unnecessarily forgone. African governments would be better placed ‘racing to the top’ by strengthening institutions and rule of law, clamping down on corruption and investing in public services that develop human capital, attracting investment without forgoing revenue.

Stopping the bleed of capital flight

The onset of the pandemic saw a wave of capital flight from African economies, reducing the resources available to governments to tackle the crisis and highlighting the ongoing challenge this issue presents to African governments.

Capital flight occurs when the value of assets and capital is shifted from one country to another, often from developing countries with volatile currencies and political instability, into more advanced economies with hard currencies, such as dollars or euros, or to tax havens. This decreases the taxable revenues available to government and weakens domestic currencies, which in turn increases the cost of imports, government investment and debt servicing. Capital flight is so prevalent across Africa that the continent has been rendered a net creditor to the rest of the world. Related losses between 1970 and 2015 across 30 African countries outweighed the combined stock of debt owed and foreign aid received over this period.

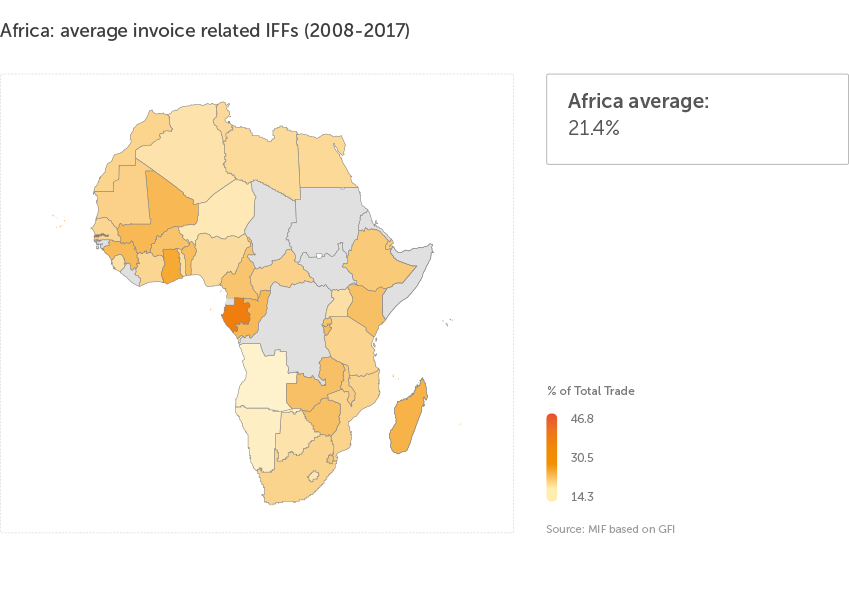

Illicit financial flows (IFFs) are of particular concern and must be halted. IFFs represent capital flight through illegal channels such as the appropriation of public funds into shell companies by corrupt officials or trade mis-invoicing by importers and exporters to evade customs duties, VAT and income taxes. UNCTAD estimate that between 34 and 59 percent of all capital flight comes from trade mis-invoicing, while Global Financial Integrity data show mis-invoicing to have cost $107.6 billion per year across 42 African countries between 2008 and 2017.

Strong institutions and political stability are important in deterring capital flight. A 2020 UNCTAD report noted that capital flight was also proportionally higher among African countries with lower investment in health and education. In essence, good governance is key. However, to tackle IFFs the technical capabilities and effectiveness of specialised national institutions such as customs services, financial intelligence units, and anti-corruption agencies must be improved. Efforts made by African countries must also be mirrored at the global level through increased transparency in trade and finance, as well as renewed efforts to tackle secrecy in global financial centres.