The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA): what’s in it for Africa’s youth?

06 June, 2019

The 2019 Ibrahim Forum Report highlighted that Africa’s most urgent challenge is the fact that its massive youth bulge is mostly devoid of prospects. Around 60% of Africa’s population is currently under 25 years old, and the continent’s youth will account for twice Europe’s total population in 2100. However, demographic and economic trends are not in tune. Whilst important, the economic growth of the last decade has been mainly jobless, and Africa’s youth consider unemployment by far the most pressing challenge for their governments to address.

Besides hindering the potential of Africa’s biggest resource, its human capital, lack of economic opportunity is also a key driver of African migrations, which are mainly composed of young, educated people. In some cases, this absence of prospects can also influence young people to join extremist groups. These urgent challenges can only be addressed by African countries, and the AfCFTA is seemingly an important step towards this.

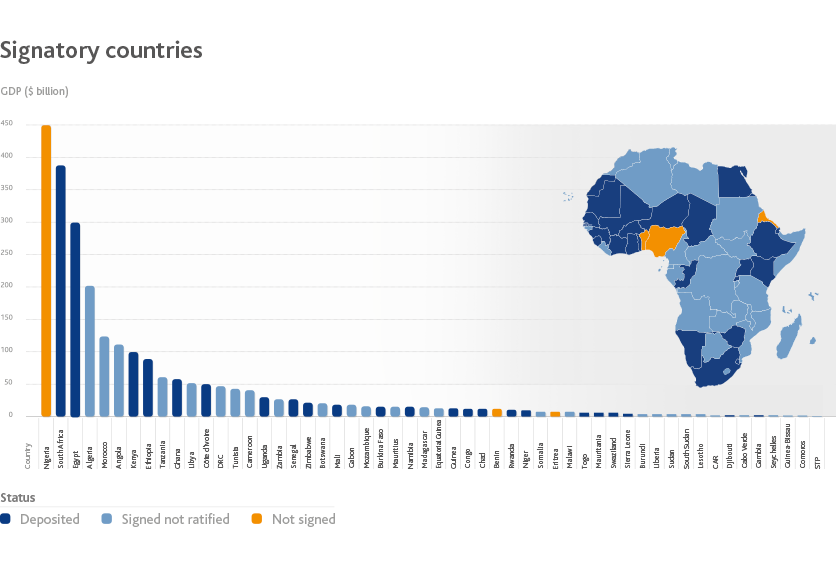

The AfCFTA is a trade agreement between African Union (AU) member states, aiming at creating a single continental market for goods and services as well as a customs union with free movement of capital and persons. The agreement was signed in Kigali in March 2018 by 44 member states (now 52) and entered into force on 30 May 2019. Its operational phase will begin in July 2019, becoming the largest free-trade agreement in terms of participating countries since the establishment of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). Only Benin, Eritrea and Nigeria are yet to sign this agreement. These three countries contribute 18.6% of Africa’s GDP and16.5% of its population.

Under the AfCFTA, expanded markets and unobstructed factor movements – labour, goods, services, capital and persons – should promote economic diversification, structural transformation, technological development and facilitate quality job creation. The full implementation of the AfCFTA would eliminate all tariffs, likely to generate welfare gains for Africa estimated at around $16.1 billion, even after deducting tariff revenue losses. Africa’s GDP is expected to grow by 1% and total employment by 1.2%. Intra-African trade is expected to grow by 33% and Africa's total trade deficit to be cut in half. If successfully implemented, the AfCFTA could generate a combined consumer and business spending of $6.7 trillion by 2030.

AfCFTA has the potential to redress some of the key challenges the continent is facing, provided that adequate investment is allocated to maximise Africa’s biggest resource – its human capital.

A single African market will provide a conducive environment for easing one of the biggest obstacles the continent is facing: professional mobility and skills portability. There is immense potential for the continent to exploit, considering that the majority of African migrants choose to stay on the continent and 70% of sub-Saharan migrants move within Africa. However, for many businesses in Africa it is often easier to employ a skilled non-African expatriate than a skilled African expatriate. For instance, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the number of different visas required (entry, exit, working establishment) is considered burdensome. In Nigeria, the eligibility criteria for a visa for a skilled worker are considered too demanding, focussing on formal education levels rather than on experience gained through work.

Limited or weak frameworks for recognition and compatibility of skills, educational and experience qualifications across national borders remain a key issue for the continent. This hinders the ability of migrants to enter and effectively engage in continental labour markets. South Africa has historically granted work permits aimed at attracting high-skilled professionals from SADC member states to address labour shortages. The country has adopted a policy to raise immigration levels of high-skilled workers with the Critical Skills Work Visa, which is issued in accordance with the 'critical skills list', a list of occupations in high demand. Moreover, bilateral labour agreements between South Africa and SADC member states facilitate the mobility of miners and construction workers. Lesotho, Mozambique, Swaziland and Zimbabwe supply much of the labour force in the construction sector in South Africa.

Other fundamental elements would be to ease policies for upskilling the workforce and educational mobility. Africa’s capacity to adapt to the requirements of the future labour market relative to the region’s exposure to future trends leaves very little room for complacency. Africans must be equipped with future-ready skills to engage in new professions, such as ICT or tourism, or make the most of underexploited sectors such as agriculture and agri-processing. Moreover, only 22% of African students studying abroad choose an African destination. The high number of African students leaving the continent to study abroad remains a key issue. These students enjoy other opportunities in the countries where they study, making it a challenge to attract this human capital back to the continent and to foster educational mobility within Africa.

The success of the AfCFTA will thus depend on the capacity of African governments not to neglect the potential of human capital. In light of this, the continental agenda for trade and business expansion should be reinforced to allow professional and educational mobility, and upskilling of Africa’s workforce. This will help to ensure Africa’s youth are given the economic opportunities they deserve.