Making Futures: Jobs and Innovation in an Emerging Africa

16 February, 2026

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the Mo Ibrahim Foundation.

“To secure the future, African countries must lay the foundation for the continent’s economic transformation by designing and creating knowledge societies” Kingsley Chiedu Mohalu.

Burst or Build?

Over the past decade, policymakers, economists, and development institutions have repeatedly highlighted Africa’s youth bulge as both a demographic opportunity and an employment challenge.

Africa currently boasts of around 532 million young people (broadly defined as ages between 15-34). The three largest economies, Nigeria, South Africa, and Egypt, together account for well over 70 million of them. At the same time, the continent is also projected to see a net increase of roughly 740 million working age-people by 2050, with about 12 million young Africans entering the labour market each year.

The 2015 Global Entrepreneurship Monitor report cautioned that “Young Africans are three times more likely than adults to be unemployed. And in a region where 62% of the population is under the age of 25, serious interventions are needed to ensure that the youth have access to jobs which are sustainable and, crucially, that lead to more jobs for others.”

But unemployment figures alone do not tell the full story.

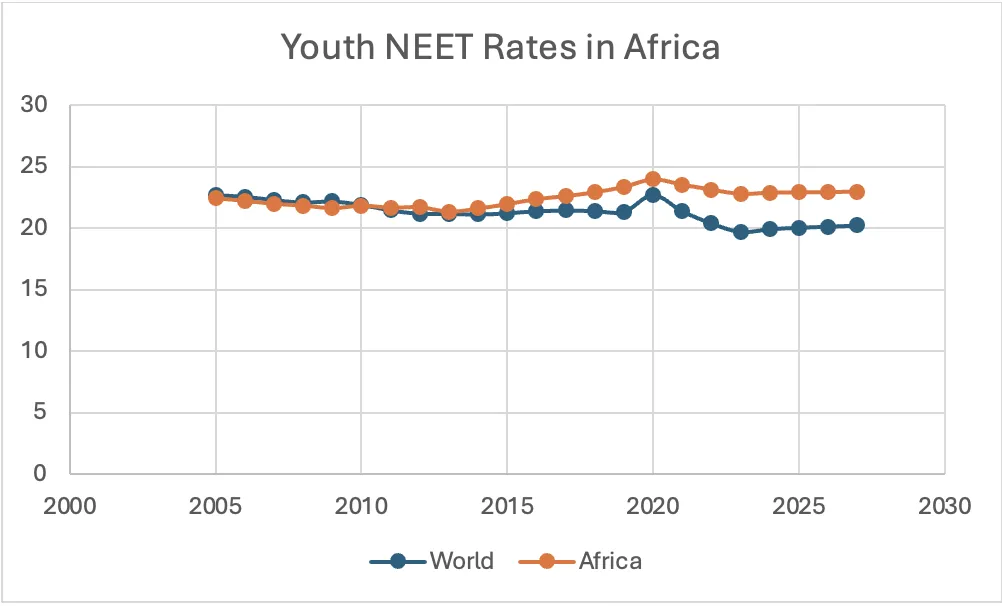

The youth NEET rate (the share of young people not in employment, education, or training) remains persistently high. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), youth not in education are those neither enrolled in school nor in formal training programmes. NEET rates have been slow and uneven across the continent.

Source 1: Authors chart based on ILOSTAT

Yet work in Africa has several faces. When we look more closely at youth employment data, the picture becomes starker.

African youth may not always be formally employed, but this does not mean they are not working. What is colloquially called “the hustle” often translates into early school dropout and entry into the informal economy, navigating work without contracts, with low and unstable pay, no social protection, and limited upward mobility.

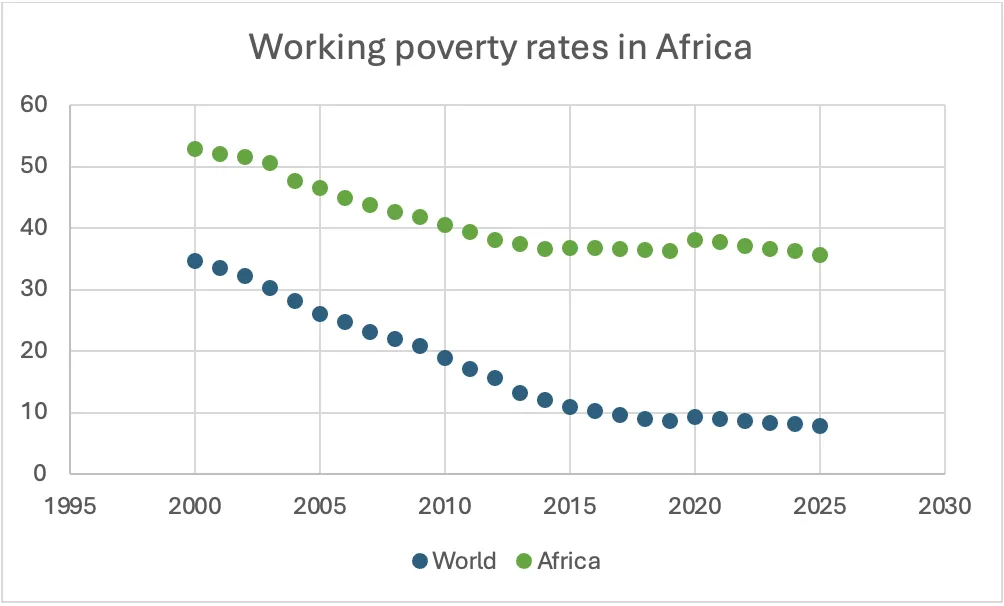

Research also shows that although African youth enter the labour market earlier than their peers elsewhere, nearly as many 15 to 17 year-olds are working as are studying. Among those working, 96% hold informal jobs, and around 40% live below the international poverty line.

As of 2025, roughly 90% of employed young Africans about 273 million people work in informal jobs, predominantly in low-productivity agricultural sectors. The result is widespread working poverty, defined as employment while living on less than US$2.15 per day. Africa’s working poverty rates remain significantly above the global average.

Source 2: Authors chart based on ILOSTAT

This is not merely a jobs crisis. It is a productivity crisis.

Furthermore, with rising mobile internet penetration, smartphone adoption, and digital platforms, the gig economy has expanded rapidly. It has redefined full-time employment and introduced new forms of work: short-term, task-based, platform-mediated engagements that are either web-based (freelancing, content creation, online teaching) or location-based (ride-hailing, delivery services, home services).

For many young Africans, gig work has become a transitional pathway into income generation. Yet without appropriate regulatory frameworks, it risks entrenching precarity rather than unlocking productivity.

The youth dividend

To convert Africa’s demographic expansion into genuine economic dividend, possibly the largest in modern history, there must be a decisive shift from fragmented initiatives to coherent, market-shaping strategies. Human capital development must align with structural transformation so that economies generate jobs that are productive, stable, and dignified.

With the right strategy and sustained investment, this generation of Africans could significantly increase productivity, expand domestic consumption, attract long-term investment, and accelerate economic transformation across the continent.

Innovation is essential. But innovation alone is not enough.

What Africa needs are ecosystem builders, institutions and enterprises that create the systems within which innovation can scale. Upgrade supply chains that allow for the transfer of capabilities across to related sectors. Platforms that connect talent to markets. Infrastructure that lowers barriers to entry. Capital that flows patiently into growth sectors. And policies that reinforce, rather than fragment, progress.

The youth dividend will not emerge from isolated projects. It will be engineered through coordinated systems that convert demographic momentum into durable economic opportunity.

Countries rarely jump from exporting raw commodities to manufacturing advanced semiconductors in a single bound. The capabilities required are too distant. The tree is too far.

Instead, growth happens through adjacent moves. From cocoa beans to processed chocolate. From textile assembly to branded fashion exports. From motorcycle taxis to electric mobility infrastructure.

Each leap builds new muscles, i.e. new skills, new knowledge, new capabilities, and new higher skilled sectors.

Africa’s youth dividend will not be realised by asking the frog to leap across the forest. It will be realized by cultivating a denser forest of capabilities, where each leap builds the strength for the next.

The multiplier effect of ecosystem building.

African entrepreneurs are not just creating startups. They are building systems.

Consider four examples, Style House Files, EWaste Africa, Ampersand and Golden Palm Investments Corporation:

(1) Ampersand a Rwandan electric vehicle energy technology company founded in 2016 is pioneering e-mobility solutions for Africa. Ampersand has grown from a garage bootstrapped RD project (their words) to having a fleet of over 5000 motor cycles, 400 000+ battery swaps per week, more than 500 employees, and a presence in Rwanda and Kenya.

(2) EWaste Africa an eWaste recycling company based in South Africa and founded in 2013 by Pravashen Naidoo with a mission to do more than leverage technology to process waste. Their focus and drive are to create jobs and empower communities.

(3) Style House Files, Nigerian and African fashion industry pioneer, and producer of #LagosFashionWeek, which in 2025 celebrated its 15th anniversary. Founded by Omoyemi Akerele in 2011 to support African creativity. LFW has grown to become Africa's largest and most influential fashion event, often showcasing over 60 African designers, and in 2025 was named a finalist for the Earthshot Prize.

(4) Golden Palm Investment Corporation “GPIC” a Pan-African investment holding company backing African entrepreneurs and start-ups. GPIC has a portfolio that includes Flutterwave, Jetstream, Andela and mPharma and has raised over $1.2 billion in venture financing. GPIC was founded by Sangu Dalle in 2008 (whose book “Making Futures: Young Entrepreneurs in a Dynamic Africa”, in part inspired the title of this blog).

Across fashion, mobility, waste, and capital, we are seeing a new generation of African companies redefining what job creation looks like. Not factory-line industrialisation alone. But ecosystem-driven opportunity.

All four have leveraged on technology to formalise structures where infrastructure is limited, build low-emission industries and create platforms for others to thrive. Different sectors. Same structural effect: they create jobs by building platforms others can thrive on.

Why trade policy is important to ecosystem builders?

Efficient trade policy at the national, regional, and continental level can address labour and capital mobility needs of ecosystem builders, and trade coordination and cooperation across borders is paramount for this to happen.

Ecosystem builders create the platforms, infrastructure, and networks that allow innovation to scale. Trade policy determines whether those platforms remain confined within national borders or expand into continental markets. When trade regimes incentivize value addition, reduce cross-border friction, and support regional integration, they amplify the job-creating potential of ecosystem builders. When misaligned, they constrain it. The youth dividend depends not only on innovation, but on a trade architecture that supports ecosystem builders who in turn allow innovation to compound.

Conclusion

The future of work in Africa is being engineered locally. The African Business Forum is the perfect platform for ecosystem builders and political leaders to agree on tangible steps for cooperation and continuous dialogue on how to build on this momentum. After all, only the wearer of the shoe knows where it pinches.