Measuring Free and Fair Executive Elections in the 2017 IIAG

25 October, 2017

As Kenya’s Supreme Court set a new precedent by annulling the presidential vote held last August citing irregularities, a recurrent debate on democratic elections as essential ingredients for governance is accentuated. In the past decade Africa witnessed several elections, with peaks of 15 a year in 2011 and 2016. However, as the regularity of elections in Africa increases, so does the lack of trust by African citizens in electoral processes. According to Afrobarometer, only one-third (34%) of Africans across 36 African nations believe that their vote is always counted fairly, and only 25% of citizens have a high degree of trust in the national electoral commission.

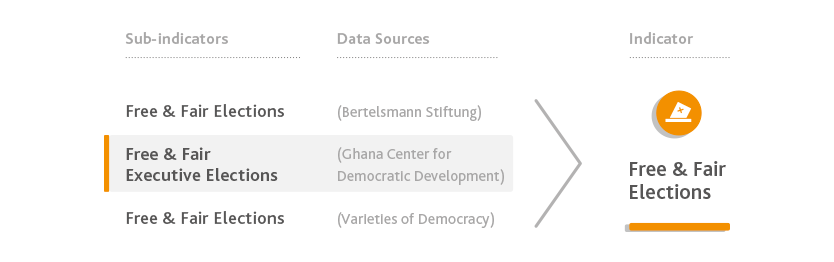

Acknowledging the importance of assessing not only the regularity, but also the quality of electoral processes across the continent, the Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG) includes a sub-indicator named Free & Fair Executive Elections from Ghana Center for Democratic Development (CDD-Ghana). Together with two additional sub-indicators, provided by the Bertelsmann Stiftung (BS) and Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem), these three clustered variables constitute the indicator Free & Fair Elections that sits under the Participation sub-category in the Index.

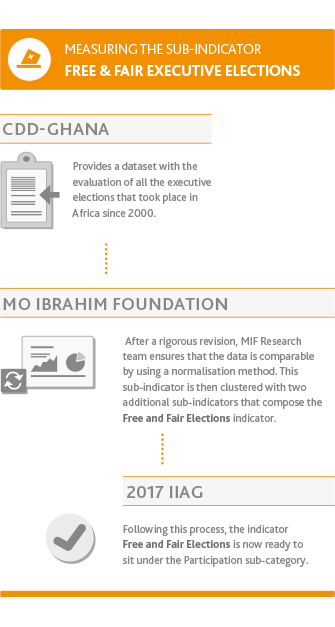

As part of its efforts to address the data paucity in Africa, the Foundation commissions the data from CDD-Ghana. CDD-Ghana is an African independent, nonpartisan and non-profit research-based and policy-oriented think tank, promoting rule of law and integrity in public administration. By including this source in the IIAG, the Foundation offers an intra-continental assessment of the quality of electoral processes in Africa. Every year, CDD-Ghana provides to the Mo Ibrahim Foundation the African Electoral Index updated dataset, evaluating African executive elections since 2000.

What do we mean by free and fair?

At this point you might wonder: how exactly can the quality of an election process be measured? CDD-Ghana evaluates executive elections under three measures: Free and Fair Executive Elections, Opposition Participation in Executive Elections and Transfer.

- In Free and Fair Executive Elections there are five underlying measures assessing the degree to which the electoral procedures – pre, post and during the election period – were followed, as well as if voters have access to electoral information and are granted the right to vote without any intimidation. This variable also questions if candidates are granted the right to public demonstrations, meeting and freedom of speech.

- Opposition Participation in Executive Elections has five underlying measures that capture if all political parties are able to participate and if the election leads to a peaceful turnover of power.

- Considering that there are cases where elections could serve the sole purpose of lengthening the stay of power of the same political group and/or leader, the measure Transfer assesses whether as a result of elections power is transferred completely, partially, or not.

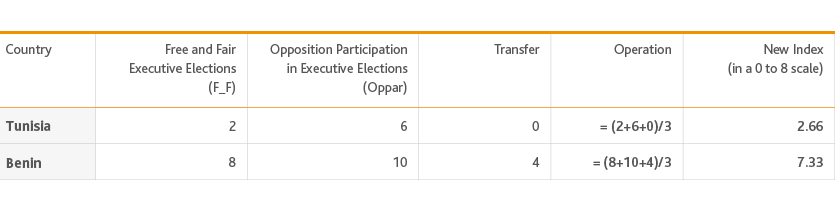

All the underlying questions within the first two measures are answered in a scale from 0-2, in which 0 is given when major irregularities are found in the electoral cycle, 1 when some flaws are noticed and 2 – the best score – when very minor irregularities occur. On occasions when a disruption of the electoral cycle occurs, such as a coup and/or the postponement of an executive election to over a year, the country is then penalised by receiving a score of 0. On the other hand, Transfer is assessed on a scale from 0 to 4, in which 0 is assigned when there is no change of party and leader, 2 is given when a new party or a new leader is elected, and 4 corresponds to a new political party and a new leader taking power. The sum of all the scores given are then divided by 3 leading to the final result which highlights a country electoral performance.

Let’s practise!

So, let’s take the recent presidential elections in Angola as an example – how would CCD-Ghana assess their electoral cycle? After an extensive literature review of local and international news outlets the underlying measures would be rated on a scale from 0 to 2, 2 being the best score. For instance, if the electoral procedures, pre-election were followed with very minor flaws, Angola would score a 2 and so on. Bearing in mind that a country’s maximum score would be the following: 10 points for Free and Fair Executive Elections (if a country scores 2 in all 5 questions), 10 points in Opposition Participation in Executive Elections (if a country scores 2 in all 5 questions) and finally 4 (maximum score in Transfer). This value would sum up to a maximum of 24 points to be divided by 3, which is why the raw data potential range is 0-8.

Once the data collected goes through a rigorous revision, does that mean they are ready to be made publicly available? Well, not yet. One of the features of the IIAG is that it enables users to benchmark governance performance across various dimensions at national, regional and continental level, which is only possible if the data used is comparable. Consequently, the CDD-Ghana dataset must first go through a standardisation process of called normalisation. This statistical process transforms the initial scores from a scale of 0-8 into common units in a 0.0-100.0 scale, where 100.0 is the best possible score.

To improve the accuracy and robustness of this indicator measurement, the Free & Fair Executive Elections sub-indicator from CDD-Ghana is clustered with two additional sub-indicators provided by Bertelsmann Stiftung and V-Dem. Hence, different nuances and dimensions of this matter are being captured. This creates the Free & Fair Elections indicator, composed of three sub-indicators from different data sources in which CDD-Ghana is included.

Read a more detailed explanation on clustering variables and normalisation on our previous blog about how we construct the Index.

So, what happens next?

The inclusion of the Free & Fair Executive Elections sub-indicator from CDD-Ghana enriches the related indicator. Likewise, it contributes to a broader debate on the extent to which African countries are truly committed to ensuring that the quality of the elections held meets the continental standards and their citizens’ expectations.

If you want to learn more about the performance of the continent in this indicator and the results of the 2017 IIAG, do not forget to access the Index on November 20, freely available at iiag.online.