Spotlight 11: Why Africa needs a New Public Health Order to tackle the threat of infectious diseases

By Diego Fernandez Fernandez, Senior Analyst

COVID-19 has shown how infectious diseases constitute a serious threat to health, global economies and security, respecting no boundaries.

Africa’s burden of endemic and infectious diseases, the largest in the world, poses a significant threat to the continent’s aspiration to achieve its long-term developmental blueprint ‘Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want’. One of the most important lessons from the pandemic is the urgent need to invest in the continent’s healthcare systems not only to improve health, but also to secure economic development.

Health still ranks low in African governments’ priorities

Research Spotlight series

A new series exploring data and key findings from the 2021 Ibrahim Forum Report.

The 2021 Forum Report, assessing the impact of COVID-19 in Africa one year on, highlights how progress on prior commitments and frameworks, such as the Abuja Declaration and the Africa Health Strategy 2016-2030, has not been sufficient to address the structural weaknesses in Africa’s health systems. For instance, only seven countries have met the target of spending 15% of their government budget on health in at least one year since 2001, when African Union (AU) member countries made this pledge in Abuja, Nigeria. In 2018, the latest data year, no African country managed to meet this pledge.

Universal Health Coverage (UHC) means that all people have access to the health services they need, when and where they need them, without financial hardship.

As highlighted by Dr Tedros Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO), during the 2021 Ibrahim Governance Weekend, the pandemic has underlined the importance of investing in Universal Health Coverage (UHC), based on primary healthcare and strong community engagement, for global health security. While all African governments have committed to achieve UHC by 2030, in 2019 only ten of them provided their citizens with free and universal healthcare (Algeria, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Gabon, Mauritius, Namibia, Rwanda, Seychelles, Tunisia and Zambia).

Almost 80% of respondents in MIF’s 2021 Now Generation Network (NGN) survey state that citizens in their countries face obstacles to accessing free and universal healthcare. Over 90% cited lack of health capacity and almost 80% cited costs as the main obstacles to healthcare.

As a consequence, domestic private spending on health is higher in Africa than in the rest of the world. In 2018, domestic private health expenditure as a share of current health expenditure (CHE) in sub-Saharan Africa was more than 10 percentage points higher than the global average (51.4% and 40.3%, respectively), and out-of-pocket health expenditure amounted to, on average, 33.3% of the CHE, compared to a global average of 18.1%.

Out-of-pocket payments are spending on health directly out-of-pocket by households.

The limits of international cooperation have been exposed

The COVID-19 pandemic has also revealed how fragile international cooperation can be when the world is collectively threatened and challenged by a common disease threat. The ease with which Africa was left out of the COVID-19 diagnostics market demonstrated how easily global cooperation and international solidarity can collapse.

With the rise of global protectionism and vaccine nationalism, Africa has found itself at the end of the queue for access to any available vaccines. As shown by the Bloomberg Covid-19 Vaccine Tracker, as of 16 September 2021, African countries account for just 2.2% of the COVID-19 vaccine doses administered globally, despite accounting for nearly 18% of the world’s population. Furthermore, as indicated in the latest update of MIF’s COVID-19 in Africa tracker, two African countries, Burundi and Eritrea, have yet to start their COVID-19 vaccination campaigns.

A New Public Health Order to cope with 21st century disease threats

Dr John Nkengasong, Director of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (AfCDC), says Africa needs a ‘New Public Health Order’ to be more resilient and cope with 21st century disease threats. This new order would help the continent fight a set of concurrent health challenges that interact synergistically (the ‘syndemic’) and contribute to its excess disease burden, including: rising rates of non-communicable diseases, emerging and re-emerging infections, and endemic diseases. Africa’s rapid population growth, as well as the threats posed by environmental, climatic, and ecological changes, are among the major factors driving the ‘syndemic’.

The New Public Health Order calls for “cross-continental and global collaboration, cooperation, and coordination”, and should be based on four pillars:

-

strengthened public health institutions

-

strengthened public health workforce

-

expanded and strengthened African manufacturing of vaccines, diagnostics, and therapeutics

-

respectful, action-oriented partnerships.

According to Dr Nkengasong, a New Public Health Order is needed to fight the inverse care law, a principle that prevails in Africa today. The inverse care law states that the availability of good medical or social care tends to vary inversely with the need of the population served.

The Partnership for African Vaccine Manufacturing (PAVM)

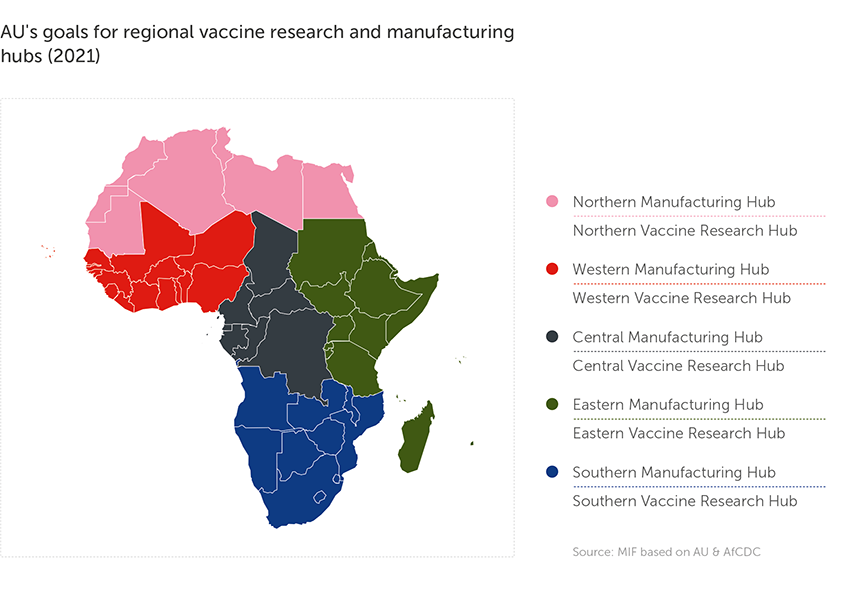

A major outcome of the AfCDC-AU conference on vaccine manufacturing in April 2021, the PAVM aims at achieving the third pillar through:

-

agenda-setting and coordination

-

establishment of regional vaccine production hubs (one in each of the five African geographical regions)

-

resource mobilisation and financing partnerships

-

strengthening of regional vaccine regulatory institutions

-

technology transfer and workforce development.

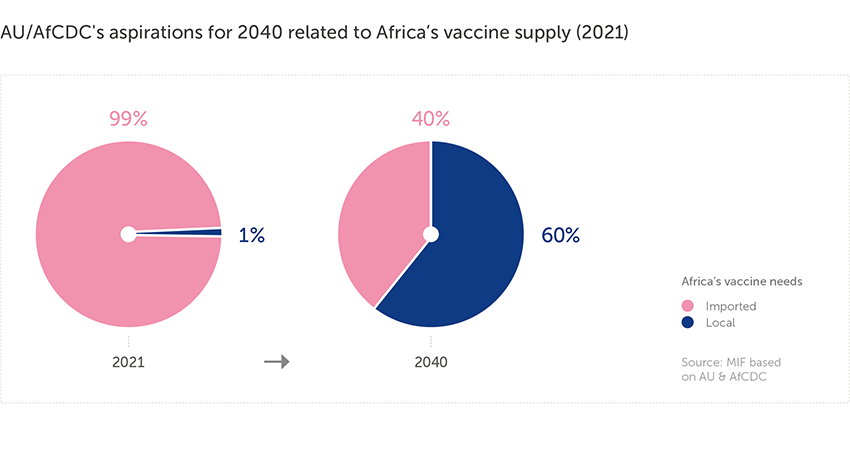

Despite representing about 25% of global vaccine demand, Africa still produces less than 0.1% of the world’s vaccines and about 99% of its routine vaccines are imported.

In addition to the short-term goal of administering COVID-19 vaccines to 60% of Africa’s population by 2022, the PAVM aims to deal with the continent’s wider vaccine needs, including:

-

vaccines for known African pathogens: local production of 100% of vaccines needed for at least 1-3 emerging diseases, such as Ebola, Lassa fever and Rift Valley fever by 2040

-

vaccines for unknown global pathogens: local capacity to manufacture 30-60% of vaccines needed for a pandemic by 2040

-

routine immunisation: local capacity for 20-60% of annual production of routine vaccines needed.