The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not reflect the opinions or views of the Mo Ibrahim Foundation. This article was originally published by The Conversation on 23 January 2019.

Q&A with David E Kiwuwa, Associate Professor of International Studies at the University of Nottingham, and Ibrahim Scholar Mandipa Ndlovu

The Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG) measures and monitors Africa’s governance performance. It produces an impartial picture of governance performance in every country on the continent. David E Kiwuwa, associate professor of international studies at the University of Nottingham, asked Mandipa Ndlovu, a Zimbabwean academic, researcher and 2018 Ibrahim Scholar to unpack some of the findings from the 2018 report.

Where do you see progress in Africa in terms of good governance and leadership over the past decade?

The Index defines governance as the provision of the political, social and economic goods and services that every citizen has the right to expect from their government. Governments have a responsibility to deliver these services to their citizens.

For countries that have done well in Overall Governance, common improvements have been seen in the category of Safety & Rule of Law – notably the sub-category of Transparency & Accountability. Here, the continent is in a better position than it was 5 years ago, though National Security needs to be reinforced if the continent is to improve the average Safety & Rule of Law score.

The Health measure has improved in 47 countries over the past ten years with African average improvements in several areas like Antiretroviral Treatment (ART) Provision (+36.3), Absence of Child Mortality (+15.5), Absence of Communicable Diseases (+7.3), Absence of Maternal Mortality (+4.8), Access to Sanitation (+3.3) and Immunisation (+2.9).

In spite of this progress, Africans are not satisfied with their governments' handling of basic health services.

Additionally, improvements in Infrastructure (+4.6) are a positive indication that physical and industrial development is taking place across the continent – this will in turn facilitate human development.

Where is progress slowest?

Gender is one area of concern. The 2018 report notes that gender representation in politics has improved. However, the empowerment of women in general has registered a slowdown. Gender representation, therefore, must not be conflated with gender empowerment.

The data also shows that policies and representation do not always translate into action. South Africa, for example, continues to face high rates of femicide and patriarchal ideals within its judicial structures. This is despite its liberal constitution.

While the country shows great improvements under Women's Political Participation and Representation of Women in the Judiciary, there is a decline in Women's Political Empowerment. Women are well represented in the country's cabinet, for instance, but there's been a marked deterioration in how empowered ordinary women feel to participate in politics.

Such disconnects are concerning.

However, countries like Rwanda must be commended for their deliberate inclusion of women in places of influence. Interventions like these are still too rare on the continent. A critique of the blueprint used to understand gendered participation on the continent is necessary.

Also worrying is the lack of progress under Sustainable Economic Opportunity, the worst performing measure. Almost half of the continent's citizens (43.2%) live in a country that's seen a decline of sustainable economic opportunities in the last 10 years. Parallel to this, the population of Africans in the working age bracket (15-64) is expected to grow by +27.9% over the next ten years.

Why have African governments struggled to translate economic growth into improved sustainable economic opportunities for their citizens?

Trends indicate that transparency and accountability are vital for sustainable economic opportunity in the long term. Greater accountability and transparency is needed on national expenditure, for example.

The IIAG highlights that the indicator measuring Sanctions for Abuse of Office scores its lowest African average in 2017 (41.6). Protectionist systems that allow for the abuse of power and inhibit the levelling out of socio-economic disparities must be exposed. Only then can these systems be reformed to open up more opportunities for all. Increasing access to sustainable economic opportunities improves human development. This in turn allows for innovation in health, technology and other spaces that increase the overall functionality of good governance.

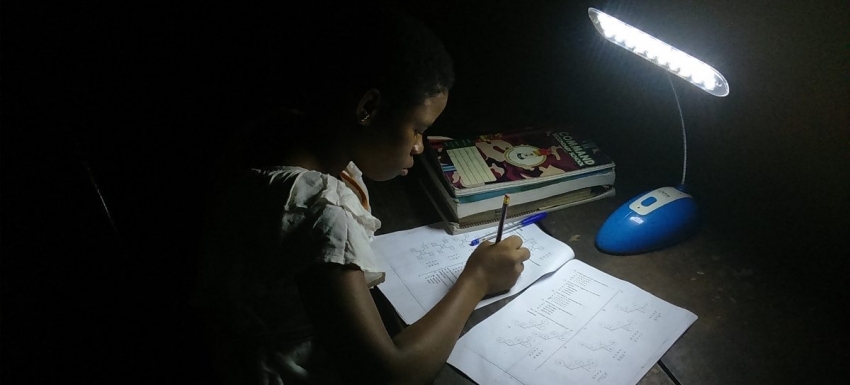

What role can education play in improving governance?

The gaps in African governance are twofold: socio-economic inclusion and education. It is important to focus on both areas to bring about overall improvement. Although improvements have been recorded in the sub-category of Participation in the last 10 years, student and youth resistance movements belie the progress.

The rise of populist movements coupled with the lack of voter registration within the youth dividend must not be misconstrued as political apathy.

It is unacceptable that the continent's growth remains jobless. In South Africa for example – where the 2018 index was launched – there is a critical skills gap that has not been adequately addressed. The quality of education in South Africa is worrying.

Also in South Africa, as well as the rest of the continent, youth enrolment in schools is improving. But Education Quality, Satisfaction with Education Provision, and Alignment of Education with Market Needs are persistent causes for concern.

Education has a great bearing on sustainable economic opportunities because skilled workers feed the market. Africa is currently experiencing a skills gap deficit. With 27 countries registering deteriorating education scores in the last five years there is a further decline to already fragile sustainable economic opportunities.